Candy wheels around our mother

For a little over a week after the rapid decline of my mother and her friends’ concerns brought me to my mother’s, I was in a state of shock – it all felt so surreal – and I felt a desperate urgency. I was on the verge of tears much of the time and I felt depressed, especially in the mornings. But now Mom is relatively stable. Greatly diminished in capability, without much quality of life, but she’s not getting visibly, or at least quickly, worse. We have slowed down, at least for now, into a grueling day by day of uncertainty and trepidation. And a lot of sleeping.

November 6, 2014

“Oh, you’re up!” she says. Her speech is a mumble, and not much above a whisper. “Took you long enough. What time is it?”

“Eight.”

“Oh, then you can go back to bed then.” She begins to sing. “You just called to say you love you.” A word was off and the tune was off. She sings it again.

“It’s ‘I just called to say I love you,’” I say. I sing it.

“That’s not the right tune,” she says. “It’s a country song.”

“It’s a Stevie Wonder song.”

She looks at me for a moment. “It’s a country song too. I think. Of course I can’t remember who it’s by.”

* * *

I’m on a client call but my ears prick up. Is my mother calling? Something doesn’t sound right. I open the bedroom door to see her vomiting into one of the blue bags we keep around. Meanwhile, my client wants to talk about his strategy for an interview with McKinsey & Co.

Afterward I come out to find that Mom’s old friend from Rangely, Linda Berry, has arrived to spend the day. Linda, who was a nurse for thirty years, is applying lotions to Mom’s back and straightening out the folds in her shirt to minimize bedsores.

Mom says to me, in her murmur, “Was Brianna here yesterday?”

I already dread answering her. Brianna is Mom’s granddaughter. She lives in Alabama.

“No,” I say. “She wasn’t here.”

Mom’s eyes fill up with tears.

“But you may have felt her here,” I say. “Or maybe you met her in a dream.”

“I’m losing it,” she says.

* * *

She is cold. I lay her featherbed on top of her blanket and lean down to add the heat of my body in an embrace.

“Do you need anything else, Mom?”

“What I want,” she says, her voice breaking, “I can’t have.”

I hesitate. Would it hurt to ask?

“What is it you want, Mom?”

“To get up,” she says, and now she is crying.

I lean down and cradle her head in my arms and put my face against hers. “I love you so much, Mom.”

“I’m sorry,” she says.

“For what, Mom?”

“Always on you,” she says.

* * *

Linda reminds Mom of some of their happy times. Going to the Sleepy Cat Ranch near Meeker for a fine dinner where “we were treated like ladies. So nice to live in Rangely and be treated like a lady.” And did we remember the time both women and their kids went up Dragon Road, above Rangely, to try to cut down a Christmas tree with an axe whose head fell off after every swing? Or the night, very late, when Mom had diarrhea and had run out of toilet paper, and neither one of them had enough gas in their cars to do any more than drive to work the next day, so they both set out walking and met halfway so Linda could hand my mother a roll of toilet paper.

“It was always amazing to me how she could just toss together such a wonderful meal,” Linda says. “It would take me all day and still wouldn’t be as good.”

They were both in Montrose together from 1987, when Mom arrived from Steamboat Springs four years after Linda, to 2002, when Linda moved back to Rangely. After Mom’s divorce in the late 1990s, and before I bought her the house she now lives in, she bought a trailer. “She bought that little trailer and she put it on a credit card, until a week later when she got a bank loan,” Linda says. “She always found a way. She was just so . . . and she still does, up to this very latest when she can’t do her own stuff. Very independent.”

This morning Mom’s abdomen was in great pain and she wanted to take a bath. I told her I had a coaching call and wouldn’t be able to help her out of the tub. She said, “I can get out. Independence is so important. Just being able to move a finger on my own.” She demonstrated the finger movement.

* * *

How did humans endure the end-stage ravages of cancer without painkillers? They must have been in such terrible pain that they’d just ask someone to kill them with a rock.

* * *

Where are all the men? It’s fascinating. Compassion, caretaking, and leave-taking must be women’s work.

Another day in which my depression is at bay. I wonder if my depression was being caused by my resistance, as well as the suddenness of it all, and whether now I have inevitably become more accepting of something that is no longer new, and that shows no signs of reversing itself.

* * *

I read about a study. “Mass General study demonstrated the value of palliative care. Two groups of stage 4 lung cancer patients were given the standard oncology treatment, but one had a series of conversations with a palliative care specialist. The latter group chose fewer days in hospital, stopped chemotherapy sooner, went in hospice earlier and suffered less. They also lived 25 percent longer.”

* * *

At about 1:30, Mom asks for salad. Adam doesn’t think we should give her salad. Adam and I take forever to go out and buy it and prepare it, but when she puts the first forkful in her mouth, a smile spreads across her groggy features and she gives a thumbs-up.

The hospice nurse just can’t believe Mom is eating salad. She’d told her yesterday that she should have only clear broth until she hasn’t vomited for 24 hours. Salad is too rough, too hard to digest! The nurse also tells Adam and me about the restlessness shown by people shortly before they die – lots of wants and needs, nothing satisfies. She says that’s the stage before the “transition” phase, wherein the patient comes to accept the reality of dying. I feel my attention wandering away from the topic.

“But she’s not ready for that,” the nurse says. “Some people go quietly, and some fight tooth and nail. That’s your mother. She’s angry. She’s really pissed off. I would be too. So maybe she won’t be able to go with acceptance, maybe she will.”

It makes me indescribably sad to imagine Mom passing away while sad, angry, or afraid, rather than at peace. As I think about it, I realize I always assumed she would accept death before it comes. I pictured her patting my face, a weak smile on her own, and telling me it was all right, it was all going to be right.

* * *

I lean in to hug Mom.

“I haven’t seen you all day,” she murmurs. (Of course she has). “Come here.”

We hug like that for a while. I pull away for a moment. “I’m so sorry this has all happened so fast. It must be very disorienting.”

She nods. “I’m not sure where to go from here.”

* * *

Mom says, “I keep thinking they’re going to tell me what to do. I think I’m being taken away.”

“By who, Mom?”

“Like kidnapping,” she says.

Oh my. Is this the confusion stage, which comes not long before death, or is this medication?

“I’m always asking where you are,” she says. “’Where’s Chris?” she said, using my old, and middle, name. “Where is he? I want to know where you are.”

* * *

“I know more about nutrition,” Mom says, defiantly, as some of us talk about what the hospice nurse said. Meanwhile, Linda says she learned long ago to give the patient what she wants.

* * *

She’s more groggy than usual, even less coherent or alert. I think she’s sleeping more, too. Whatever the cause, she sometimes asks childlike or confused questions, or makes non sequiturs. Again I wonder if this is the confusion phase, or she’s just medicated. But she’s no more medicated than in the past. She’s certainly not pressing her pain pump more, because we track that. Maybe it’s the confusion. ☹

* * *

Her eyes open. “Should I go to my bed now?”

“Sure, if you want to. Do you want to go now?”

She nods. Adam and I take all her things into the room, and then we support her weight as she sort of walks to her bed. She gets in and I begin to throw Oma’s wool blanket over her top sheet.

“I’m sad,” she says.

I pause and look at her. “I’m sad, too, Mom.” I climb up and hold onto her. “What are you sad about?”

She says something vague that I’ve forgotten. Then she says something about money with X’s on it.

“Maybe that’s why I’m agitated,” she murmurs.

“Why, Mom?”

“Because I need to get to the money.”

* * *

“Do we have enough money for the cab?” she asks. It is as if she is relaying the content of her dreams in real-time.

Eyes closed, she lifts her left hand and wiggles it.

I say, “Plenty of money, Mom.”

She nods, satisfied.

* * *

She seems to be in more pain, and we press the button on the bolus more often. Somehow she has kept down the salad she ate.

She picks up the vaporizer pen in one hand and a lighter in the other. She seems on the verge of trying to light the pen, as if it were her glass pipe, when I take the lighter out of her hand. Another time, she seemed unsure which end of the glass pipe to put to her mouth.

She is confused. She is irritable – is that similar to being agitated? The hospice books say that confusion and agitation happen when the patient has one to two weeks to live.

* * *

Adam picked up Candy at the airport. I was on a conference call with my team at Physician Cognition. Adam told me that when Candy went into the bedroom, he could tell that Mom knew who it was before she opened her eyes. Then she opened her eyes and they touched one another’s faces. I had wanted to be there to see them see one another again.

Candy says to me, “This doesn’t seem real.”

* * *

November 7, 2014

“It’s so surreal,” Mom says, “that we’re sitting here talking about death and dying.”

“It is surreal, Mom. That’s exactly what it is.”

She begins to weep. It hurts me to see this kind of pain, such bald-faced fear and disorientation. I hold her head against my chest. “I know it’s all been so sudden, Mom. It’s happened very fast.” She presses her head against me. “But you’ve been so brave, and you’ve touched and inspired so many people.”

I think of one of my favorite pictures of her. It’s in brown and white. She is wearing a skirt, and she’s on a scooter. In this picture she always looked to me a little like Anne Frank – her age, her face, her hair, the optimism of her smile, her boundless humanity. Her hands are on the steering column of the scooter. She’s leaning forward, standing on one leg with the other pointed straight behind her. On her face a beatific expression, evidence of the capacity for joy so rare in the rest of her family. “What a life,” I say, “for that little girl from Erlangen.”

“I was always on the move,” she says, waving her hand slowly. “Couldn’t sit still.”

* * *

At other times she is still not coherent. There are the non sequiturs, the questions she knows the answer to. When we don’t hear her, and we say so, she is irritated and repeats herself, or shakes her head, with annoyance. In other words, the sort of thing I would do.

* * *

She wants to go out for a walk, so we three bundle her up and I carry her to her

Candy and Mom

wheelchair out front. We go to Main Street but she is cold and wants to go left for one block and then back home. She could already taste some hot tea. I did take some pictures of my mother and sister that I’m very fond of.

* * *

It broke my heart to see her just sob with the pain from her bedsore. Candy was already sitting on the bed near her. I once again cradled my mother’s head in my arms and told her how sorry I was, and how courageous she was. But then I found one of those donuts that air travelers put around their necks to help them sleep. I fitted it under her, with the open side pointing behind her, so that her tailbone area was suspended. She felt instantly better.

* * *

I find that I still don’t have bottomless reservoirs of patience with her, but I do have nearly continual compassion for her. I attend to her quickly, I coo and call her sweetheart, I hug her and kiss her and comfort her. I’m always asking if she needs anything. I move with alacrity, just as I once admired my friend Julio doing, seemingly for everyone he met on the Camino de Santiago. I have probably done more of all this for my mother in the last eleven days than in all the rest of my life with her combined. I feel a little badly about that.

I wish Candy could stay here to go through this with me, with Mom, with us. With the original tiny family that was put asunder when I was thirteen, and my sister was taken away from me. We have never lived in the same house or even city since then. But she would forfeit her job if she stayed any longer. Forty hours is all we have.

* * *

Candy texts me to say she’s at WalMart. She’s looking for something for Mom, she says, maybe flowers or something that smells nice. I feel so helpless, she says, and she is so negative I was trying something positive. I wrote her back:

Yes, she’s in the irritability phase. Also all this anger and grief that she’s dying is combined with her own personality to make for some complaint. For all we know, she may also be suffering from severe depression. A lot of the symptoms are certainly the same.

To this Candy sent a frown-face icon.

I talked to Mom about metaphysics, about what I’d read and what I’d experienced and heard others experience. Beings of pure love was one that stuck out in my mind. I said we would both go to be with them, to be in their embrace of pure love and acceptance, the thing we’ve always craved most. She seconded that, saying it was hard to find. I recorded it on my phone’s voice recorder.

* * *

1:54p.m. She’s very negative right now. Everything has a tinge of annoyance – of anger, perhaps. She worries about details like repairs around the house and complains of them not being done sooner, and is anxious for them to be done soon. She worries about money. “What will it cost?” she says, when she hears that my Land Rover’s back door doesn’t close properly.

* * *

“Last time you were here, you weren’t here,” Mom says to Candy, sadly.

Unfortunately, Candy disputes this, and now Mom is both sick and not feeling heard.

“We didn’t talk about essentials,” Mom murmurs. That’s true, but Candy again resists.

“You might want to give some on this, Candy,” I say. “Mom did ask you guys several times to look through photo albums with her and nobody did, and she said even at the time that everyone was always on their phone. So it’s valid, even if it’s not a serious crime.”

But her anger, the bitterness, the sadness is hard to hear. It’s hard for me to feel. Silke says, “I can totally understand her. She tried her best and did so many difficult things and she hoped it would be enough. But it wasn’t.”

Yes. I think Mom feels cheated, betrayed by hope. To stay alive for so long, she had to have outsized, even unrealistic expectations about living, and very little thought of dying. “I know this is a surprise,” I’d told her earlier. “It really surprised us. And I know that’s scary.”

* * *

The hospice nurse arrives. Suzanne. Candy is also sitting on the couch. Suzanne examines the pain medication pump that Mom drags with her everywhere.

“She’s used twice as much medication in the last twenty-four hours,” says Suzanne.

Not long afterward, Mom begins to cry. I go to her and hold her. I am crying too, for the first time in a day or two. She looks at me and looks into my eyes. I look at her and want her to see only love.

“Did you hear that?” she says. “It’s double.”

“Is that why you’re crying, Mom?”

“It means,” she says, “I’m going to die sooner.” She weeps.

* * *

Mom says she thinks her unsteadiness could be due to her medication. Suzanne disputes that, gently but firmly. “It’s not your medication, Inge.”

“Well we don’t know what the problem is,” she says.

“Mom,” I say, “we know that the cancer is spreading in your body. It’s getting into organs and pressing against nerves, and it’s causing such pain in you that you have to take pain medication constantly. It’s making you vomit when you eat most food.”

Suzanne says, “Inge, I know you’re angry, and I get why. I do.”

“No, I’m not angry,” Mom says, and in a fairly typical Momism, she adds, “Sometimes I’m just pissed off” – she takes a breath, and then tears fill her eyes – “because I did everything right.”

Ah, there it is. I fight back tears to see such vulnerability and pain, such crushing disappointment.

“You sure did,” we all say. “You worked and tried hard. You did everything right.”

“I just need to take some time with this,” Mom says, her voice small. “Everybody is telling me what’s going to happen but I need to feel inside myself and see for myself.”

She cries for some time, on the way to the bathroom, and on the way back, once she gets into bed.

“You leaving doesn’t sound good, either,” Mom says to Candy.

“I know, Mom,” Candy says. “It doesn’t sound good to me either.”

* * *

Suzanne tells Mom she’s leaving, Mom smiles warmly and thanks her. Suzanne kisses her on the head. “I know you don’t want to hear it,” Suzanne says, “but you just need to relax. If you keep being angry and fighting it, it’s going to shorten your life.”

“I didn’t have a lot of time to adjust,” Mom says.

“No you didn’t, but, whatcha gonna do now? You just need to relax, sweetie. Find your way into this new place.”

* * *

“Our world doesn’t exist without our mom in it,” Suzanne is telling Candy. She’s on her way out the door. She had told me the same thing a few days ago. She encouraged me to seek out support or talk to their counselor.

Today was a day of reckoning.

I’ve pushed out of my head any notion of the grieving I will do afterward. To think of that, on top of everything else, would be too much. I know I can only imagine the pain I will feel from the loss of my mother, from the suffering she endured, from my remaining guilt. But one day at a time.

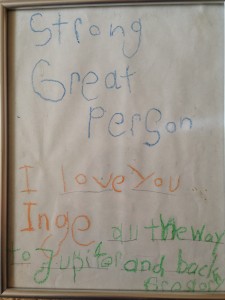

Mom’s young friend Gregory gave this to Mom a few years ago