Wednesday November 19, 2014

Today she is more exasperated than ever. Irritated to repeat herself, explain herself, or be asked any question. The non sequiturs are more frequent, and in fact have become the great majority of what she says. Petty worries. Simultaneously vocally unhappy with her pasta and upset that she has to risk hurting someone’s feelings by saying so.

The confusion often manifests as arbitrary and impossible commands, such as to add hamburger meat that we don’t have to a bowl of spaghetti that’s already before her. She tells Adam how to add salt and pepper to a meal.

* * *

“Where are all the boxes?” she asks, looking around her.

“What boxes?”

“The boxes that got all this stuff here.”

“You brought this stuff here over the last eleven years, Mom. This is the same little house you’ve always loved.”

“Is it still 512 North 3rd Street?”

“Yes, same address.”

* * *

I say aloud that today would be another good day to do some work at Starbucks. Mom is being helped off her portable commode. She says, “What I want you to do first is go through my cabinets. I don’t have . . . much life left.” A few minutes later she is sobbing and being comforted by hospice’s certified nurse’s assistant (CNA), Bonnie (not to be confused with Mom’s friend Bonnie).

After Bonnie the CNA has gone, Mom says, “She says it won’t be long anymore.”

“What won’t be long anymore?”

“This . . . thing.”

What the hell? “Who told you that?” I gather she means Bonnie. I need to have a talk with her, or her bosses.

“We need to talk about some things. My funeral.” She puts her hands to her face and begins to sob. “This is so hard.”

* * *

She repeats some words from a poem that she wants read at the Irish wake (my words; she calls it a memories party) we will put on for her. I find the poem online and read it to her with a firm, measured cadence, so that she may feel the truth of it:

Do not stand at my grave and weep.

I am not there. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry;

I am not there. I did not die.

— Mary Elizabeth Frye

“To save a wretch like me,” Mom adds.

“Amazing Grace,” I say.

“I did it my way,” she says.

“Elvis,” I say. “Are those the songs you want us to play?”

She nods.

* * *

Linda struggles to put marijuana salve on Mom’s bedsore. Her hands are cold and the touching probably hurts. Mom begins to cry. I go to her and comfort her and say I’m sorry.

“Oma took only eleven days,” Mom says. “She didn’t cause trouble for anybody.”

“Neither are you, Mom.”

* * *

She is crying. “I don’t know how to do this,” she says. I can still hear the pitch of her voice rising throughout her sentence.

I don’t say anything for a while. I think of saying nobody does, but I’m not convinced that’s true. I think of Zen masters and yogis I’ve read about. There are people who train their minds for death, such as the Tibetan Buddhists whose text, Bardo Thodol, is called, by Westerners, the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Relying in part on training to cultivate lucid dreams and wake oneself up from them, the meditator who masters the Book’s techniques can remain conscious as she crosses the threshold into death, and can remain conscious after the body has died. And of course I have heard of regular people who feel they had a good life, enough life, and are ready to go.

I say to her, “Do you remember what you’ve always said about relationships? ‘Let go with love’?”

She nods. To my left Linda is already agreeing.

“I think that’s what you do. Love and forgive yourself, love your loved ones, try to feel love in place of fear.”

* * *

She hasn’t slept this morning at all. She is concerned about many things, and she is very weepy. Is this the “restlessness” the hospice books speak of, which means “days to hours” left?

* * *

She asks if I have any questions for her. She doesn’t want me not to know things. I say I will ask her if I think of any and she says something about running out of time. “There’s no big deal,” she says. “Even if it seemed like that when you were young. You have good DNA.”

* * *

I look up to see her gazing at me as she lies in her bed. I look back at her and smile. She continues to look at me very intently, and then she turns her head and starts to cry.

* * *

I am less weepy myself, and more – what’s the word? Numb? Detached? Accepting? It has occurred to me that I will feel much more sadness after her death simply as a by-product of thinking about the past more: about things she did (and we did) and things she said. Nostalgia is just memories of what is no longer possible. That’s why the word in Greek means a return to pain rather than undiluted happy memories.

* * *

“What are your plans for the day?” she asks me.

“I’m going to stay right here with you,” I say. “I’m not leaving.”

* * *

She is concerned that the stained glass window has been removed from the living room. There was never such a window.

* * *

It’s nearly 5p.m. and she has slept very little today. One of the books hospice left a few weeks ago is called “When Death is Near: A Caregiver’s Guide”. It says in there that with “days to hours” to live, the patient becomes agitated, restless, and may have a burst of energy.

Is this that?

* * *

My mother is, in many ways, already gone, already lost to me. And I am stricken by her crying from sadness, or fear, or her broken-hearted disappointment. I fear that will stay with me palpably and for a long time.

* * *

I wake her up to take her medication. I ask her to turn over onto her other side. Then she is crying.

“What is it, Mom? Are you hurting?”

She nods.

“Where does it hurt?”

“All over,” she says, weeping. “It’s like it’s every cell.”

Oh, wow.

I show her where the bolus is and where its button is, and we press it. Two beeps, a pause, and then another beep. .20 ml of hydromorphone is injected into her port. We recently increased the hourly dose from .15 ml to .25 and she’s still hurting enough sometimes that we have to press the bolus one to three times in a short period of time. The cancer is on the move.

* * *

To be unable to think and express oneself clearly, and yet still be able to feel physical and even psychological pain. To be losing one’s mind but sentient enough to be aware of it and suffer. Hardly seems fair, does it?

* * *

A few moments later she spies the emerald-green couch next to her bed. “Who brought that couch in?” she asks.

* * *

And later, she is clearly exhausted and says something I can’t understand, followed by “and just get it over with”.

“That’s why you’re going to a better place, Mom. Because this is just miserable for you.”

“Do you have to leave tonight?” she asks.

I think my tone is at least as important as what I say. If I sound unworried, caring, protective, then the content that she may not understand anyway becomes less important. Now I say, “No, I’m staying here all night, with you. I’m going to sleep right over there on that other couch so I can keep an eye on you and make sure you don’t have too much pain.”

And she is satisfied.

Thursday November 20, 2014

At about 3:50a.m. I hear her groan. I am sleeping on the couch with the bolus a foot away. Whenever I hear her in pain, I click the button she has forgotten how to even find. Now I give her a milligram of Ativan. She is fairly alert, even asks Adam to fetch her coffee, which he now makes like an expert.

During much of the discussion that follows, she is often crying or sad, but I will refrain from adding that fact to every thing she says. By the same token, I will also omit most of the times I had to ask her to repeat herself so that I could hear or understand her.

When she asks questions these days, she is utterly guileless, and trusting. She’s like a child. The things she asks about seem to me to be like a list of her anxieties and concerns.

“I can’t tell you how shocked I am,” she says, and this is when she begins crying. “I don’t want to be here.” And then: “I’m trying to hold on to my sanity.”

Not long afterward, she says she needs to call the dentist to get a replacement for the lower dentures that we seem to have lost. “He has it on file,” she says. She doesn’t like how the lack of dentures slurs her speech. As with her threats to return her crappy phone, this notion of having the time and need to have new dentures made betrays her fleeting moments of reflexive denial. It’s the life force in her.

* * *

She asks something about our life together. I mention that she was always loving to me. For forty-seven and a half years.

She looks at me with amazement.

“Really? You’re that old?”

I say I’ve been with her for over two years, in Montrose and in Telluride. Before that I was in Portland, Seattle, Bend, New Jersey.

“That’s quite a resume,” she says. She looks at me. “How did I luck out so much?”

I just want to turn everything around to be about her. “You deserved it, Mom. You deserved every good thing that has happened to you.”

“You’re a good man,” she says, as if she were just learning it.

“You raised me,” I say. She smiles.

“Do we have cows?” she says.

* * *

She looks to her left and sees Adam. “What are you doing here, Adam?”

“I came here to visit you,” Adam says gently. “And Cameron. But mostly because marijuana is legal in Colorado.”

* * *

She stirs. “Is there an inheritance story behind this?”

“Yes,” I say, though there isn’t yet. “It’s a good story.”

“Is there a headline?”

A what? Sure. “Yes.”

She leans back. “A blessing,” she says. “Health, a little money. Love.”

* * *

At times she sounds like Samuel Beckett.

“We’re not the worst, are we?”

“No, we’re not the worst.”

“I mean, our standards is good, right?”

“They are very good.”

* * *

“I think it’s a memory recovery that I need,” she says. Still holding on.

* * *

“I want to know everything.”

* * *

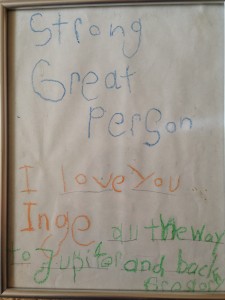

Mom, Adam, Cameron

* * *

And later, when she sees me sitting to her right: “Where’s Cameron?”

“Cameron’s right there,” Adam says. Adam and I exchange looks.

* * *

“I keep missing people. I don’t know why I keep missing people. And my brother just died, right?” She cries.

“Yes,” Adam says. “Horst died a few months ago.”

She looks at me. “You were everybody’s Swiss darling.” I’m not sure what this means. And to Adam: “You’re my best coffee warrior.”

* * *

She comes out of another reverie to ask, “Do I have to have assistance in dressing?” As if she were trying to be briefed on her own life.

“Do you want assistance, Inge?” Adam says.

“No, I want to know if I can dress myself. Am I able to.”

“I think a little assistance is helpful,” Adam says, rather than saying “no”.

* * *

“Do you want to sleep?” I ask her. It’s the middle of the night. I sure do.

“I don’t want to sleep,” she says. “Bits of my life are falling away. If I have one.”

* * *

“Do other people have beds like this?”

“No, Mom, you have a Swiss Army knife of a bed. The nicest in town. It’s like a smartphone.”

“I don’t know how to use that,” she says. “I’m a geriatric idiot.”

“No,” I say, “you’ve never been an idiot. You’ve always been quite clever.” Adam seconds the motion.

* * *

“What’s the situation?” she asks me. “How did you react? I mean, did I fall?”

“No, you didn’t fall. Your cancer has just been spreading.”

“Do we have a lot of good steady friends, too?”

“Yes, very steady,” I say.

“A lot of friends,” Adam says.

She cries. “That’s good to have,” she says, wiping her eyes.

“It’s great to have,” Adam says.

“We can raise a barn,” Mom says.

“Yes, we can raise a barn,” he says.

“But I can’t walk.”

* * *

She opens her eyes, looks at me.

“You’re a great mom,” I say.

“Am I a great other things, too?”

“Sure you are. A great cook—“

“A great friend,” Adam says.

“A great walker,” I say.

* * *

It’s about 4:30 a.m. Adam leaves for the airport shortly, so he’s packing quietly as Mom talks.

* * *

She says she’s very fastidious and so wants an easier way to go pee on her own, without calling to anyone else first. I can’t gather what she is saying, but she seems to be designing some kind of contraption. I tell her that’s not necessary.

“I’m almost always here, so you just have to ask me for help.”

She brightens a bit. “Are you a gentle person?”

“Yes,” I say. “Why?”

“Because I’ve had it so rough.”

* * *

Out of nowhere, I hear her breaking the silence in the room to say, “Do we have a father?”

* * *

Sometime after saying something, she stirs. “Is that a true thought?”

“Yes,” I say. I can see that she’s upset about her cognitive deficits. “You have many true thoughts.”

She reaches for my hand. “My soul seems to want to find you.”

* * *

Before I can ask her about this, there’s a knock at the door. It’s Bonnie, come to take Adam to the airport. Mom cries as Bonnie hugs her. “I’m having a snot or identity crisis,” Mom says. “One or the other.” Later she looks at Bonnie. “I can’t remember you.”

“I’m Bonnie,” says Bonnie.

* * *

Gesturing in my direction, she says to Bonnie, “I didn’t know what to call him for a while there.”

“You can just start with ‘son’,” Bonnie says.

Mom’s eyebrows go up. “I wasn’t sure,” she says, almost conspiratorially.

* * *

Silke arrives at about 10:30a.m. I had been trying to go back to sleep, thinking it was earlier, but I get up. Mom tells Silke that she hadn’t known who I was. “I thought, That’s a handsome man there.” A little later my mother says to me, “I sure hope I like you.”

* * *

And then one of those exchanges that I will carry with me.

“I just feel like bits and pieces,” she says, sounding so sad. “Are they ever going to come back together?”

“Yes, Mom. They will come back together. And you’ll be much happier.”

“Soon?”

Sigh. “Yes, soon.”

* * *

She has been sitting in bed with her eyes closed. She stirs. “I was thinking, that as soon as I get back on my feet” — Silke and I look at each other — “maybe out of pride, I can make a walkway, an elegant one, so I can get around the house.” She points at the walls and draws an imaginary railing or something. “Because people do challenges,” she says, as if answering an objection.

Mom and I have both moved into new stages. She can no longer walk or support her weight. Getting into and out of bed is slow and painful. Moving four feet to the portable commode can exhaust her to the point of nausea. Until ten or so days ago, she only got nauseated during the relatively much longer and more arduous trek to the bathroom. She sleeps most of the time. And perhaps most distressingly, she is disoriented, confused, and very sad.

I began in an agitated state of fear and sadness and desperation. But three and a half weeks on, I seem to have settled in. It’s grueling, my conditioned mind offered up the other day. No, not grueling, I think, It’s not that bad. I exist at a surely temporary equilibrium. Even the morning depression seems to have lifted. I suspect I am able to maintain this balance only because it is too soon, perhaps even impossible, to feel what I will later come to feel I have lost. Too soon for the bittersweet memories of a bygone era. Too soon for any regrets. Even too soon for the sadness I fear I will always feel about my mother’s weeks-long psychological distress.

When her cognition was still in place, my mother expressed a pained dumbfoundment about her situation. “How did I get here?” Now that her reality comes and goes as fluidly as a dream, when she says “How did I get here?”, she literally doesn’t know where she is. The anxiety about her sudden illness has changed to a more metaphysical anxiety about place and existence.

* * *

Hospice nurse Suzanne is late to a meeting that includes the hospice-provided social worker. I can feel people gradually becoming more concerned about me. Adam suggested that I hire outside help. Mom’s friends say, “How are you holding up?” I don’t know. I don’t know what to compare it to. I catch the end of Mom complainingto the social worker about losing her mind, when she says, “Is it Alzheimer’s? Do I have Alzheimer’s?”

“No, honey, you don’t have Alzheimer’s,” the woman says. “It’s just the progression of the disease. The cancer causes the organs to shut down, and the brain is another organ, so it’s going to be affected too.”

“It’s normal, Mom,” I say. I know what she needs to hear.

“It is?”

“Totally normal. There’s nothing wrong or bad about it.”

She seems relieved.

* * *

Suzanne and the social worker have come to tell me what to expect, and they ask me if I’m comfortable taking my mother to the bathroom and cleaning her up if she’s incontinent. I have a simpler answer: “I’m pretty sure my mother wouldn’t be comfortable with that.” Adam, Suzanne, and the social worker suggest that I hire someone – Adam has even offered to pay – to help me. But I can’t figure out, and no one, not even the home care expert Suzanne recommended, can explain to me how I could use such a person. I don’t need or want someone here all the time, or even predictable periods of time, and what I would want – someone on call when something less predictable happens – is not what they offer.

* * *

I talk to her of the afterlife. As to heaven or an afterlife, I am agnostic – I don’t have particular beliefs, nor do I reflexively (like an atheist) disbelieve. (I do disbelieve hell). But I set all this aside now and paint a picture from the near-death experiences I know Mom is familiar with. The social worker who has come to talk to me helps.

I tell her something like, You will always be connected to me, Mom. You won’t miss me because you’ll always be able to be with me. But I will miss you because my soul is going to be stuck in this falling-apart body a while longer. You are moving on to the next Camino. The next stage.

“But all alone,” she says, mournfully.

You won’t be alone. You’ll be able to be with Candy all the time, and Brianna, and Carrie and Jannilyn and Gregory and Annika – but also Oma and Uncle Horst. You can travel wherever you want to go, just like you always wanted to do, and feel the presence of everyone you want to.

* * *

I am explaining to Monika that we were up at about ten to 4 in the morning, and that Bonnie came at about 4:30 to take Adam to the airport. Mom takes this in. “Boy,” she says, “we’re busier than a whorehouse.”

* * *

She says she’s going to bed. It’s a little after six. For the next four hours I surf Facebook, the web, my emails, and my journal.